Book

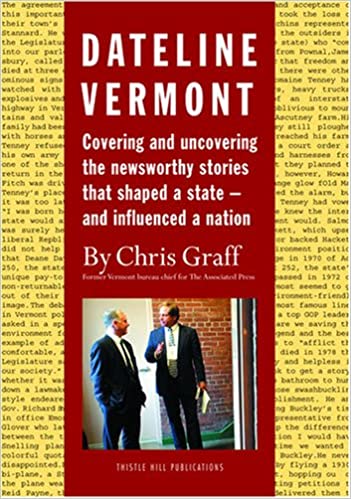

Dateline Vermont

by Chris Graff

The inside story of how Vermont transformed itself from a rural, Republican outpost into the state of Howard Dean, Jim Jeffords, Pat Leahy and Bernie Sanders

Journalist Graff writes a memoir from the frontlines of the state's history-making events

December 7, 2006

by Randolph T. Holhut, Staff Writer

The Brattleboro Reformer

BRATTLEBORO — For Vermont's history buffs and political junkies, the go-to reference book has long been William Doyle's "The Vermont Political Tradition," but that book hasn't been updated since 1987, and much has happened in Vermont since then. Until Sen. Doyle gets around to doing a revision, we have Chris Graff's new book, "Dateline Vermont."

That Graff wrote this book was an accident. In a perfect world, he'd still be the Montpelier bureau chief of the Associated Press, a job he held for 25 years until his abrupt and controversial dismissal by the AP in March of this year.

The terms of his severance agreement bar him from discussing why he was terminated, but leaving the AP gave the 53-year-old Graff a chance to step back and examine the three tumultuous decades of Vermont politics that he witnessed as a reporter.

Besides summing up the people and events that shaped Vermont history, Graff mixes in a bit of memoir into this book — starting with the culture shock of going from suburban Connecticut to rural Vermont in 1965 when he was 11. When he first saw the hill farm of his new stepfather in North Pomfret, "I thought I just arrived at the end of the world," Graff writes.

Graff arrived just as Vermont was undergoing its most wrenching changes. The interstate highway system was in the midst of being built, and the Vermont House had just undergone reapportionment. Until 1965, every town in Vermont sent a representative to the House, meaning towns as small as Grafton or Halifax had as much power as Burlington or Rutland. When the federal courts ordered reapportionment, the House went from 246 member to 150 and the clout of the small towns was gone forever.

That, Graff writes, was the first step toward Vermont going from Republican bastion to one of the most liberal states in the nation.

Younger readers may not realize that Vermont went more than a century without a Democratic governor until the election of Phil Hoff in 1962. Or that the House never had a Democratic speaker until Brattleboro's Timothy O'Connor in 1975. Or that there wasn't a Democratic majority in the House until 1977.

Graff watched that transition, starting when he was at Middlebury College as a reporter at the campus radio station in the early 1970s under then-news director Jim Douglas (yes, that Jim Douglas).

Graff entered Middlebury as a drama major but soon found there was more drama in the political arena than the stage, and switched his major to American history.

"I'm not sure what came first — my love of politics or of journalism — but I grew up in a house where we didn't eat dinner until Walter Cronkite had told us, 'That's the way it is.'"

After graduation, Graff went to work for WFAD Radio in Middlebury. His work caught the attention of the AP's Montpelier bureau chief, John Reid, who talked Graff up to his bosses in New York. After two unsuccessful attempts at landing a job, Graff got in on the third try and never left.

Graff figures he's written about six million words about Vermont since he started working for AP in 1978. Within two years, he was the bureau chief. Despite several offers by the AP to work elsewhere, Graff stayed in Vermont. As a result, the AP benefitted from having the institutional memory and long relationships Graff has with the state's political leaders over the last three decades.

Being with Richard Snelling, the first governor Graff covered full time, "was like being invited to a seminar on the presidency taught by FDR and JFK," writes Graff. "Everyone who met Snelling — friend or foe (and there weren't many in between) felt the strength of his overpowering personality."

Graff and Snelling butted heads often, but Graff came away respecting him for "his strong belief that leaders should lead, without regard to how controversial their decisions should be" and for "his assumption, which seemed naive in a politician, that logic and reason guarantee success."

And then there was Madeleine Kunin. The state's first female governor was the anti-Snelling, in Graff's view. "Kunin's style of governing made her vulnerable to criticism. ... She was soft-spoken, controlled and polite, in contrast to her predecessor's bombastic personality. She did not want to be just a governor, she was determined to be a woman governor, and she brought to the office stereotypical feminine qualities of accommodation, a desire to please and non-confrontation that sometimes worked for her and sometimes against."

Snelling returned to the Statehouse in 1991 after Kunin decided against running for a fourth term. Vermont was facing its worst financial crisis since the 1930s, and it was Snelling and Democratic House Speaker Ralph Wright who cobbled together a package of spending cuts and tax hikes that enabled the state to weather the financial storm.

But Snelling never lived to see that triumph. His sudden death from a heart attack on Aug. 14, 1991, thrust into power a little known and little regarded doctor from Burlington, Lt. Gov. Howard Dean.

"It's hard to remember today how little we all thought of Dean when he assumed the governor's office in 1991," writes Graff. "Most insiders saw him as a lightweight. And a liberal one at that. When he assumed office, he fixated on balancing the budget, but many regarded this as a political necessity already set in stone by his predecessor. Analysts predicted the true tax-and-spend liberal would emerge once he won election in his own right. It never did. As the years passed, the Dean of 1991 remained: a fiscal conservative, a social moderate and a friend to business interests."

But the Dean years proved to be filled with controversy, including the two most divisive issues of the past decade — education funding and civil unions.

The debate over legalizing same-sex marriage in 2000 was particularly bruising, and Graff writes that the stepped-up security in the Statehouse that year "seemed distinctly wrong. ... Vermonters had always been able to wander in and out of every room. ... Lawmakers had done their work free of fear. Now all that changed."

The vote in favor of civil unions cost many lawmakers their jobs that fall and gave the Republicans control of the House. Graff credits his old boss, Jim Douglas, for healing some of the wounds when took office in 2003.

Like many, Graff was perplexed by Dean's transformation into a political rock star when he ran for president. "He was becoming Bernie Sanders," Graff writes.

As the one reporter in Vermont who knew him best, Graff provided the corrective to the image Dean had during his presidential campaign as wild-eyed liberal. But because his son Garrett worked for the Dean campaign, and Graff refused to stop him from doing so, the AP barred Graff from writing about Dean.

Graff laments that he and his bureau never got a chance to give Vermont's Congressional delegation the coverage they deserved. James Jeffords, Bernard Sanders and Patrick Leahy certainly are the most eclectic trio of lawmakers that any state has sent to Washington.

Jeffords' decision to leave the Republican Party and become an independent in 2001 perfectly illustrates Charles Barkley's statement from earlier this year: "I was a Republican, until the Republicans lost their minds."

As "the last of the top elected officials to come from that era when everyone was a Republican ... in the span of forty years Jeffords did not change, but his party did."

As the Republican Party turned sharply to the right, there was no longer any more room for moderates like Jeffords.

We take Leahy for granted as one of the most senior members of the Senate, but Graff reminds us that before he became an icon, he had to win elections against some of Vermont's most formidable politicians — Richard Mallary and Sanders in a three-way race in 1974, a 49.8-48.6 percent win over Stuart Ledbetter in 1980, a tough race against Snelling in 1986 and Douglas in 1992. Not until 1998 and the ill-fated campaign of Jack McMullen — the Massachusetts businessman trounced by dairy farmer and part-time film star Fred Tuttle — did Leahy have an easy path to the Senate.

To Graff, Sanders is "one part revivalist preacher, two parts theater, and an equal measure of passionate ideology, all served up with biting sarcasm."

Sanders comes off less than saintly in Graff's eyes, but that could be attributed to the years of feuding between the two over coverage and the tone of stories. Yet Sanders joined Jeffords, Leahy and Douglas in penning a joint letter to AP Chairman Tom Curley protesting Graff's dismissal.

Graff doesn't get into specifics to why he got sacked by the AP, but hints that it may of had something to do with the controversy generated back in January by Bill O'Reilly and other conservative barking heads.

O'Reilly launched a jihad against Vermont because of Judge Edward Cashman's decision to give a child molester a 60-day sentence because a longer sentence would have kept the man from receiving sex offender counseling.

While the conservative media painted Cashman as a liberal softy who no longer believed in punishment, Graff read the transcript of the sentencing hearing and wrote stories that contradicted O'Reilly's version of events.

Graff was singled out for attacks by O'Reilly, but Graff was right and O'Reilly was not. January was "a turbulent time for us in the Montpelier bureau and me in particular," writes Graff, "but one that did not appear to jeopardize my job. Throughout it, in fact, I felt I had the support of the AP's corporate brass in New York."

Two months later, Graff was fired, and as he put it, "I would grieve as if some essential part of me had been ripped away."

Walter Mears, the long-time AP political reporter, once told Graff that the best job he'd ever had was when was sent to Montpelier in 1956 to open up the AP's first-ever Vermont bureau. "Over the years, I've come to understand and appreciate why he felt the way he did," writes Graff. "I could not have asked for anything better, except the ending."

But without the ending, we would have never had this book.

Randolph T. Holhut is the Reformer's editorial page editor.