Book

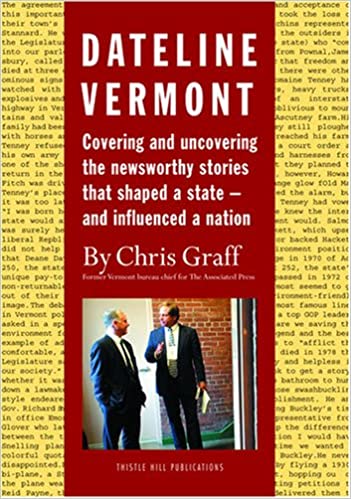

Dateline Vermont

by Chris Graff

The inside story of how Vermont transformed itself from a rural, Republican outpost into the state of Howard Dean, Jim Jeffords, Pat Leahy and Bernie Sanders

Dateline Vermont: Reporter turned newsmaker tells his story

November 26, 2006

by Kevin O'Connor, Staff Writer

The Barre-Montpelier Times Argus

On June 4, 2001, Chris Graff, flying to Washington to cover Sen. James Jeffords' historic political switch, arrived to another surprise.

As Vermont bureau chief for The Associated Press, Graff expected to see Jeffords' spokesman. Instead, the senator himself - waving a copy of Newsweek magazine with the cover headline "Mr. Jeffords Blows up Washington" - was the first to greet him.

Jeffords grinned.

"Can you believe it?" he asked Graff.

Believe what - the cover, or the fact the most sought-after man in the capital was waiting for him?

Graff figures he has written 6 million words about Vermont since his first assignment in 1971. He dispatched more than a dozen updates the morning Gov. Richard Snelling died in office in 1991. He sent an AP "flash" (even bigger than a "bulletin") when the state was the first to rule for same-sex marriage rights. He covered Jeffords and Howard Dean when the two Vermonters skyrocketed into the country's consciousness.

Then, last March, Graff made national news when the Associated Press fired him for reasons it still won't fully explain. The byline reporter suddenly found himself the stuff of a New York Times headline - as well as out of work. And so after 35 years of breaking news, he decided to write some history.

"Dateline Vermont: Covering and uncovering the newsworthy stories that shaped a state - and influenced a nation" is the long yet succinct title of Graff's new book. Now hitting stores, it's a page-turner that chronicles not only his mysterious firing, but also a flurry of changes Vermont has faced - and often fought - in the past half century.

"Half of this job I loved was to spot the change, document it and analyze it," Graff writes in the introduction. "The other half was to keep an eye on Vermont's essence and make sure it was not forgotten in the name of progress."

Graff came to the state in 1965 as an 11-year-old whose father had died nine months earlier. His mother, anxious about raising her three children alone, moved the family from Connecticut to North Pomfret - a small town near Woodstock - to marry a man she had met at her first wedding.

Growing up, Graff learned how to drive a tractor, hay a field and follow the growing season from first sap to last lettuce. Then, as a Middlebury College freshman in 1971, he was recruited by the student radio station's news director to help cover the funeral of U.S. Sen. Winston Prouty, R-Vt.

"I would learn soon enough that this news director was full of ambitious plans," Graff writes in his book. "His name was Jim Douglas. A year later, at the age of 21, he would be elected to the state House of Representatives; 31 years later he would be elected governor."

Graff switched his major from drama to American history, wrote a senior thesis about John F. Kennedy and the press, and graduated to a job at the town of Middlebury's commercial radio station. He rode his bicycle to news events and made $120 a week.

Graff occasionally drove to Montpelier to cover state government. There he got to know - and, in 1978, went to work for - the Vermont bureau of the Associated Press, which serves the state's newspapers and radio and television stations.

Graff still remembers the first sentence of his first AP story: "MONTPELIER, Vt. - 'It hurts too much to laugh and I am too old to cry,' a subdued Lt. Gov. T. Garry Buckley said Wednesday of his defeat in the primary election."

In the next year and a half, Graff worked his way from being the bureau's "new guy" to its chief. In his new role, he reported on - and faced scrutiny from - a parade of politicians. Take Gov. Richard Snelling, who taped his news conferences to make sure he wasn't misquoted. Or Madeleine Kunin, a reporter herself who became the state's first female governor.

In 1983, AP asked Graff to head its Nashville office. The offer was the first of several he'd decline. He liked covering Vermont's people, places and especially its politicians. He points to Ralph Wright, a "caricature of a caricature" Irish-Catholic Democrat who won election as House speaker in 1985 even though Republicans held a majority.

"We had both been around long enough to be cynics, but neither of us was," Graff writes in his book. "We both remained awed by the Statehouse and by governors."

But the news also could shock him. Graff reported Snelling's death in office the morning of Aug. 14, 1991, and Howard Dean's swearing-in that afternoon. Five years later, he was the first reporter to interview Snelling's widow, Barbara, just two months after she almost died from a stroke as lieutenant governor.

When Dean appointed a new chief justice to the Vermont Supreme Court in 1997, the governor chose state Attorney General Jeffrey Amestoy. At the announcement, reporters asked Amestoy when he learned the news.

"Just after Chris Graff did, I think," he replied.

Two years later, Graff wrote a "flash" telling the world that the court was the first in the nation to rule in favor of marriage rights for same-sex couples.

"In 21 years with the AP, I had never used the 'Flash' priority," he recalls in his book. "It's reserved for such momentous events as man landing on the moon and the assassination of JFK."

Graff's story would top the AP's national news digest that day. But for the reporter it was ultimately local, as he had first met the case's lead plaintiff, Stan Baker, when he worked in Middlebury in 1975.

Graff would report more national news upon Jeffords' political switch in 2001 and Dean's run for president shortly after. The journalist was the first to hear Dean's story about his younger brother Charlie, an adventurer who was captured and killed in Laos in 1974.

"We all knew that he wore Charlie's belt every day in memory of his brother - even though the big black belt didn't fit very well and often did not go with what Dean was wearing - but we knew nothing of the story," Graff writes in his book. "He choked back tears and then cried as he explained that Charlie - not he - was supposed to have been the politician."

Graff has faced his own uncomfortable moments. In 1988, Bernie Sanders, trying to win election to Congress, charged into the AP's Montpelier office with a "60 Minutes" camera crew to ask why his campaign wasn't getting more coverage.

In his autobiography, Sanders recalls of the scene: "AP was on the defensive. It was delicious." But Graff sees it differently in his own book: "My news policy was to avoid the made-for-TV news conferences in which politicians stand on farms and say we need to do more to save farmers. That isn't news; that is opportunism."

Graff had a more comic sort of communication difficulty with Patrick Leahy. The state's senior U.S. senator returned one phone call from backstage at a particularly loud Grateful Dead concert.

But the reporter's worst news day came last March 20, when he was handed a letter that began, "This is to inform you that your employment at The Associated Press has been terminated effective immediately."

Publicly, the AP has said only that Graff's firing came after he sent out an opinion column by Leahy on open government that "compromised the integrity and impartiality of the AP's news report," according to the termination letter.

Graff says his severance agreement "precludes me from speculating publicly about why I was fired." But the moment reminded him of the first sentence of his first AP story, "when Buckley said, 'It hurts too much to laugh and I am too old to cry' - except I wasn't too old to cry."

Now 53, Graff lost the professional identity that he says was "virtually inseparable" from his personal one.

"In the months ahead I would grieve as if some essential part of me had been ripped away," he writes in his book.

Then Graff received a letter from Jack Crowl, head of Thistle Hill Publications in his old hometown of North Pomfret. Crowl told him: "Your insight into the goings-on in this state and its relationship with the rest of the world would make a fascinating read."

And so Graff started writing. He begins his book by remembering a 1998 U.S. Senate primary debate between millionaire Jack McMullen and farmer Fred Tuttle. The newly transplanted out-of-stater figured he had the brains and bank account to win the Republican nomination. Then Tuttle, a 79-year-old 10th-grade dropout, asked "how many teats does a cow have?" before handing him a list of Vermont towns to read aloud.

"The candidate fell back on his French to pronounce Calais and learned like many others before him that a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing," Graff writes. "In Vermont everyone knows it's pronounced 'callous.'"

That's why the farmer beat the millionaire a week later. It's also why AP officials heard so much outrage from state readers, writers and newsmakers upon Graff's firing. Vermonters, they learned, value experience.

Graff is about to start a new job as communications chief for National Life, an insurance and financial service company in Montpelier. As a result, he'll soon leave his other public position as moderator of Vermont Public Television's "Vermont This Week" program. He'll take with him a book full of memories - and a letter written to the AP four days after his firing.

"Chris Graff is the personification of the great attributes of good journalism: professionalism, courage, steadiness, and public service by honoring the public's right to know," the letter said. "We would like to believe that attributes like these, lived day-to-day by devoted reporters like Chris Graff, will never go out of style."

Vermonters who read the signatures on the public letter recognized the names of the state's congressional delegation and governor. But Graff saw something different: The Newsweek cover boy who met him with the magazine. The U.S. senator who called from a Grateful Dead concert. The congressman who barged in with the "60 Minutes" crew. And finally, the student radio station's news director who started it all.